- Home

- Paula Woodward

We Have Your Daughter Page 7

We Have Your Daughter Read online

Page 7

After eleven years and three children, “it just didn’t work out. We grew apart,” John said. The divorce was a “real failure for me. I should have worked harder on the marriage.”

Lucinda staunchly supported John throughout the investigation of JonBenét’s murder, saying, “John would never murder his child, nor would he support anyone he thought did.”

John had been single for two years when he first saw Patsy. Enough time had passed since his divorce that he always “kind of had [his] eyes open.” He was walking to the parking lot of his apartment, and she was walking toward him. He absorbed a lot in the simple hello they exchanged as they walked past each other.

“She was attractive. Even in that glance and the way she walked, she struck me as really grounded. She wasn’t a phony, and she wasn’t trying to be sweet, just matter of fact. It was a weird sensation. She seemed like a strong woman. Someone who knew where she was going. She wasn’t flirty.”

Patsy would later state she didn’t remember the encounter, which may have contributed to why John had found her so interesting. But she had noticed him before and thought he was “good-looking with a nice smile.”

In his mid-thirties, John was a good-looking man in excellent physical shape who ran for exercise. He was quiet and had a quick laugh, dry wit and wry sense of humor. He was well rounded and versed on numerous subjects. In college, he had been his fraternity’s president. He tended to be a little serious and concentrated on getting his work done. He had a very sharp mind. When he met Patsy, he hadn’t yet had the business success he wanted.

Patsy was pretty and very smart. She’d been Miss West Virginia in the Miss America Pageant and graduated magna cum laude from West Virginia University’s P.I. Reed School of Journalism.

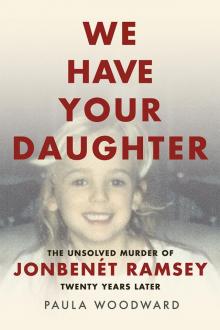

Patsy’s college photo.

Patsy also had a Southern graciousness that led her to make people around her comfortable. She had a good sense of humor, and laughter was always part of her day. Patsy loved being with others. Her friends said she was a great pal, a great mom, very loyal and supportive, a full-time friend who could be very funny.

After college, Patsy worked as a secretary at an advertising agency in Atlanta, though she found her job frustrating because she wanted to learn to handle client accounts. In the late 1970s, however, such work was still considered a man’s job. Patsy reasoned that working as a secretary in an advertising firm might eventually “open an opportunity” for her.

A week after their first encounter, John and Patsy were formally introduced when a business partner and friend of John’s happened to invite them both to dinner. When he found out Patsy was just out of college and only twenty-two-years old, John didn’t consider her as someone he would date. He did notice, though, that “she was real lively, energetic, fun” as well as “more mature” than he expected. By the end of the evening, he was kind of “intrigued” by her and “invited her to a party the next week.” Although at first Patsy found John to be “enjoyable and good company,” she didn’t think much more about him until he called and asked her out. They connected very quickly, and before long she fell in love with him because he was a “truly wonderful person, and he had honesty, character, a gentle nature, and humor, and besides, he was really attractive.” Patsy added, “I liked that he was smart, and we were ultimately great partners in marriage, as parents and in business.”

They dated for nearly two years before they married in November 1980. John was thirty-seven-years old. Patsy was twenty-four. She loved and adored his three children from his prior marriage, and John’s children loved and adored her, too, thinking of her as a “favorite aunt.”

That was another reason why John loved Patsy. That and, as he has said, she was “classy.”

The Ramsey wedding took place at the Peachtree Presbyterian Church in Atlanta, in the heart of the city’s leafy northwest neighborhoods. Physically, the church’s building recalls the movie Gone with the Wind with its massive white columns in front of a pristine white entrance, its red brick walls and towering steeple. Generations of Atlanta families have attended Peachtree, lending it an Old South resonance. The main sanctuary is soaring, filled with light and welcoming. While its side windows are clear, at the head of the sanctuary is a magnificent stained glass window that portrays the Ascension of Jesus. Huge organ pipes line the sides of the minister’s podium. “If they ever played that organ to its full potential,” John has said, smiling, “you probably wouldn’t be able to stay in the church because it would be so loud.” He has called the church a place of “comfort.” “It was a big area and we hadn’t invited many people.”

Patsy, Melinda, John Andrew, Beth and John Ramsey shortly after their wedding. © John Ramsey.

Peachtree Presbyterian Church, Atlanta, Georgia.

The Ramseys kept their wedding simple because they didn’t have much money. Patsy wore a beautiful white full-length wedding gown with an elegant train. The gown had a high neck and long sleeves that tapered near her wrists. She wore a white hat with a veil and carried red, white and yellow flowers. John wore a black tux with a red rose in his lapel. He had a full beard and mustache then. Happiness radiates from the couple’s wedding photographs.1

John remembers looking out at the huge main area of worship, waiting for Patsy to appear and “really sweating.” His son, four-year-old John Andrew, was the ring bearer. With his white-blonde hair and sporting a bow tie, John Andrew whistled as he walked down the long aisle. Everybody laughed. It was a happy occasion. John’s two daughters, the flower girls, wore green dresses that matched the bridesmaids’ dresses. Patsy remembers standing in her white gown and looking down the aisle. “I was so happy, and there was so much potential in our lives together already with three wonderful children. The steps going forward were just part of the joy.”

John and Patsy’s wedding announcement and invitation. © John Ramsey.

Their reception, which was also simple, was held at a small hotel and featured a quartet the couple had hired to play dance music. They stayed the first night in John’s home, and then left for their honeymoon in Acapulco, Mexico. John wished they could have taken his children, too.

On their honeymoon, the newlyweds quickly got to know how the other handled adversity when they became ill from food poisoning. John and Patsy were sick for two days before they were healthy enough to fly home.

At the time of their marriage, Patsy was extremely devout, while John went to church on an irregular basis and considered himself a “casual Christian.” Eventually Patsy influenced John’s interest in religion, and they both developed the faith they would rely on so much in the future.

The couple’s first home together was the Atlanta house John had bought before he and Patsy married. It was a basic, small, three-bedroom ranch built in the 1950s. John particularly liked the knotty pine paneling in the living room. He worked as a manufacturer’s representative of computer-related products. It was the early 1980s, before computers had become an accepted part of everyday life, but John had confidence in the products he sold and felt computers represented the future.

In 1982, John and Patsy bought a larger home in the suburbs of Atlanta so John could save money by working in a home office after he’d finished the basement. They made the mortgage affordable by borrowing money from Patsy’s parents. Burke and JonBenét hadn’t been born yet, but the couple had frequent visits from John’s three children, Beth, John Andrew and Melinda. John and Patsy lived in that home for the next nine years. They created many good memories there, and even today John will say, “Wish I still had that house.” They sold it to move to Boulder in 1991. Their plan was to stay in Boulder for a time and eventually return to Atlanta, which they considered home.

John always felt he was lucky he entered the computer business so early. He and Patsy began their life together by stretching their paychecks to make ends meet. But John understood the computer business and invented a software product that enabled him to be in business for himself. “Patsy was my secret weapon,” he has s

aid. “She and I would go out to dinner together with business associates. They were captivated by her and her knowledge of the business. She was instrumental in helping us get contracts and products that we needed to move forward. She was smart.”

John’s company merged with two other computer distribution companies to reduce costs and increase visibility. The consolidated company was headquartered in Boulder and called Access Graphics. Lockheed Corporation was a twenty-five percent owner. When Lockheed merged with Martin Marietta in 1995, Lockheed Martin was born, a global power-house with divisions in aeronautics and electronics as well as information, global and space systems. Eventually, Lockheed Martin bought all the remaining shares of Access Graphics, and John became president and CEO and no longer owned any interest in the company. He was now a Lockheed employee.

In January 1992, John’s oldest daughter from his first marriage, twenty-two-year-old Beth, was killed with her boyfriend in a car accident near Chicago in bad weather. John learned of his daughter’s death when his brother, Jeff, called to tell him.

“I was screaming,” John would later recall. “I don’t know if I stayed on the phone or threw it down. I just don’t remember. I stormed around my office, yelling ‘There is no God. There is no God.’ I remember screaming that out.”

John was given a ride home. Patsy hadn’t heard yet, but she knew as soon as John arrived home that something was wrong because he was so upset. When Patsy asked what was wrong, John said, “Beth was killed,” prompting Patsy to cry out and fall to her knees.

“It was just so unexpected,” Patsy later recalled. “I looked at John’s face, and he was crying. It took me a while to understand it had really happened, and then it was endless.”

Beth was John’s oldest daughter, his first-born child, and the two had a special relationship. Beth was the first of his children whom John heard say “Da-da” and watched as she learned to walk. Beth was very sensitive and compassionate. She’d worried about her dad after her parents’ divorce, called him often and always wanted to know his plans for the holidays in order to make sure he wasn’t alone. “We could talk about anything,” John has said.

One twenty-degree day in Atlanta before he and Patsy moved to Boulder, John asked who wanted to go to the lake and look at boats with him. His children looked at him “like I was nuts,” John later recalled. Then he added, “But Beth raised her hand and said ‘I’ll go.’ She always liked to go with me. So we ended up shivering in the wind, looking at boats, and had a great time.”

Beth was very mature, but very delicate. “After the divorce, I can remember her crying and saying, ‘Oh, Daddy’ when I dropped them off after a visit, which always broke my heart.” Her mannerisms touched her father’s soul; he knew that she loved him through it all. “Beth was wildly excited when we told her Patsy was pregnant with Burke,” John said. “Beth didn’t think of it as competition. It was genuine excitement. Beth saw them all as one big family that was now getting an addition as opposed to two separate families.” Beth once described herself to her dad as “a very loyal friend.” “And, you, Dad,” she said, “are one of my best friends.”

“Beth,” said her dad, “was wonderful and innocent.”

Beth’s death shaped the way John would handle tragedies like Patsy’s cancer and JonBenét’s supposed kidnapping. “With Beth, there was no chance. She was dead. With Patsy’s cancer and what we thought was JonBenét’s kidnapping, we had a chance, because there was life.”

Patsy remembered John sobbing alone in the nights after Beth was killed. Sometimes he would just break down. They both learned the best way to deal with Beth’s death was to take care of the living, the rest of their children and each other. John said there was still a terrible emptiness that took a long time to begin to heal. “It never heals completely. You still have a scar in your heart that will never go away.”

Beth, John and Patsy. © John Ramsey.

According to Patsy, “We just kept going and tried to stay positive and looked toward every new day being a better one. But life and living just aren’t the same when your child dies. The despondency is very difficult to overcome. There is always the void, and you work very hard to regain faith.”

Up until Beth’s death, John’s life had been happy, for the most part. “But happiness is circumstantial,” he said. “Happy is a four-year-old getting a chocolate chip cookie. Happy is the bill on your car being much lower than you expect when you’re low on money. The challenge became learning how to establish a deeper emotion of joy when you have such a deep scar from your child’s death.”

He began to study certain people to see how they coped with their life burdens. And he thought, “Beth’s death was my burden, and dealing with that grief was my challenge. I needed to learn to find the more steady joy again in honor of her.” He found it, in his other children, in a sunrise while on a run, in being married to Patsy, in the sound of his children’s laughter. The concept of joy wobbled within him for a very long time, but eventually it steadied. Then he built on it with memories of Beth to help him. He lived for every day and trusted less in the future.

John also felt no foreboding about the life that lay before him. He held Beth in his heart. He moved forward, step by step, until his sense of loss gave way to renewed optimism, that would too soon be crushed.

CHAPTER 6

PATSY’S CANCER

Patsy’s hair being shaved at the beginning of her chemotherapy treatment at the National Institutes of Health in Maryland, July 1993. Chemotherapy would cause her to lose all of her hair. © John Ramsey.

CHRONOLOGY

July 1993—Patsy is diagnosed with Stage III ovarian cancer in Atlanta. July 1993—Patsy is diagnosed with Stage IV ovarian cancer at the

National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. There is no Stage V.

July 1993—Patsy begins a series of experimental, last-chance chemo treatments in Bethesda, Maryland. The treatments are scheduled every three weeks.

January 1994—Patsy is found “clear” of cancer. She will undergo two more chemo treatments and then have six-month checkups until 2002 when her cancer returns.

WHEN A DOCTOR TELLS YOU that you are going to die, it swallows all else in your life. Some accept the facts. Others collapse and give in. Still others decide to fight with everything they’ve got. And not one of us knows which person we’ll be until we’ve been given that sentence.

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross in On Death and Dying lists five stages of grief or emotional behavior that people experience when told they are going to die, and their typical order. The stages of denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance apply both to those who are going to die and those who are losing or have lost a loved one. These emotions matched Patsy’s reactions to her own grief about the prognosis she was given in July 1993.

The National Cancer Institute has identified more than 200 kinds of cancer. Patsy was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. When she found out after surgery in Atlanta that she had Stage III ovarian cancer that was most likely terminal, she went into denial. She collapsed. “I tried to sleep it away. I didn’t think about my chances of living,” she said. Denial, anger and bargaining merged quickly. “Why did we lose Beth and then, why was I going to die? We always tried to live with wisdom and kindness and as Christians. Why would God give me two wonderful children and then take me away from them?”

When Patsy was diagnosed with cancer, John remembered his helplessness when he learned Beth had been killed. So he decided to take control and fight as hard as he could to save his wife. He launched a computer search for the latest treatments and experiments related to ovarian cancer. Access Graphics employees volunteered to help. They found what they thought would be Patsy’s best chance: an experimental ovarian cancer treatment program offered by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in Bethesda, Maryland.

John and Patsy flew immediately to Washington, D.C., with her medical history and a recommendation from a fam

ily friend who was a doctor. In Washington, they entered a seemingly endless maze of bureaucracy. The National Cancer Institute is on the campus of the National Institutes of Health. The NIH campus is enormous and has 27 research centers. Approximately 18,000 employees work on the main campus along with 6,000 scientists, enough people to populate a good-sized town.

Upon arriving at the NCI, Patsy and John experienced the extensive security measures that had been put in place after the first World Trade Center bombing in February 1993, when six people were killed and at least 1,000 injured after a truck bomb blew up in underground parking. Just to get into an NCI parking lot, the Ramseys had to go through two security checks that required them to show identification and step out of their car while everything was searched, including their vehicle’s underbelly via poles with mirrors attached to them.

The NCI building that Patsy and John had been directed to was a brick high-rise that was at once intimidating in size and encouraging as it represented the nation’s best cancer facility … and Patsy’s best shot for treatment.

Inside, the NCI building had a massive lobby with a high ceiling and was buzzing with activity. The lobby was filled with people waiting at elevators, doctors in different-colored lab coats and patients and visitors either coming or going. There were lecture halls. There was a large cafeteria in the basement as well as a hair salon, barbershop, history museum and transportation center. It was an enormous place. It was overwhelming. “You just didn’t walk in the front door and find a reception desk,” John said.

Patsy realized what she was in for when they first entered the building. “I lost what little identity I had and became a person with cancer,” she would later say. As she and John made their way through the facility to find where she needed to be, the people who stood out to her were the ones just like her. People with cancer. “They were in various stages, in wheelchairs, in wheeled beds with turbans around their heads. It was their eyes I noticed. Some had so much pain and misery in them. But I kept looking and I found others who were in a different place with strength and a will to live in their eyes. That helped.”

We Have Your Daughter

We Have Your Daughter