- Home

- Paula Woodward

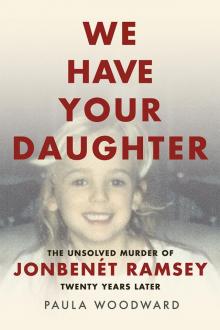

We Have Your Daughter Page 3

We Have Your Daughter Read online

Page 3

From the east-facing front of the house, the size of the Ramsey family home was deceiving. Only when you looked at it from the south did you realize how high and far back the home stretched and how large it really was, which was more than 7,000 square feet.

THEIR STORY

At about 5:45 in the pre-dawn darkness, a horrible piercing scream tore through the house.

“JOHNNNNN!!!!!!!!”

Patsy’s urgent cry hit John with an impact that caused him to flinch in alarm. His heart pounded and adrenalin rushed as he ran down the stairs from the third floor toward Patsy’s terror-filled voice.

When John reached his wife in the hall outside the open door to their daughter’s bedroom on the second floor of their home, Patsy’s face appeared stricken, her eyes wildly unfocused. She was looking at everything and at nothing. There was a ransom note, she told him, sobbing, for their daughter, JonBenét. “She’s gone!”

Fear and dread engulfed John and Patsy Ramsey as each felt a rising sense of panic in their chests and throats. It was suddenly hard to breathe.

John stared at his daughter’s empty bed. Her bed covers were pulled halfway back, and there was a crease in her bottom sheet. JonBenét’s dresser was undisturbed, its lamp and array of little-girl knick-knacks just as they should be.

The second twin bed in the room was still neatly made with a doll sitting at its head. A smaller Santa Claus bear lay on a pillow at the feet of the doll, just as it had the night before, and a few of JonBenét’s clothes had been placed on that bed.

But John didn’t notice them. He was struggling to make sense of what he was looking at. Just hours before, he had carried his sleeping daughter to her bedroom and placed her safely in her bed. He’d left the bedroom while Patsy changed JonBenét’s clothing. He then played with his son and his new toys, took a melatonin pill to help him sleep, and gone to bed.

JonBenét’s bed as it was found that morning. Courtesy Boulder Police and Boulder County District Attorney.

Second twin bed in JonBenét’s bedroom. Courtesy Boulder Police and Boulder County District Attorney.

What about nine-year-old Burke? Confusion muddied clarity that awful morning. Both parents raced to their son’s room, which was also on the second floor, on the opposite end of the hallway from JonBenét’s bedroom.

Please, God, let him be here.

He was. Burke was in his bed, curled beneath a blue bedspread. His bedroom was decorated with wallpaper featuring model airplanes.

Burke would later say in an interview that he pretended to be asleep that morning when his parents checked on him, because hearing his parents so upset had scared him.

Though John and Patsy tried to take deep breaths and think clearly, Patsy was quickly growing more hysterical and began physically shaking, her muted sobs coming in gasps. The fright kept building, tightening both their chests, and the next few moments became a panicked blur. They ran to the bottom of the back spiral staircase with its green garland decorations, where a note lay on a lower step.

The note was handwritten. In the two and a half pages of bizarrely worded threats, there was a demand for ransom.

Burke’s bed and bedroom.

Bottom three stairs of spiral staircase.

His voice rising, John told Patsy to call the police. It was 5:52 that morning. Every second was fueled by desperation.

“Hurry, hurry, hurry,” she begged the 911 operator.

John spread the ransom note on the floor of the kitchen as he tried to absorb what was in it, but most of the words didn’t make sense. One message got through:

His mind was racing. He wondered how someone had gotten into the house, and who could have possibly done this. He also started thinking about how to get the ransom money.

Why hadn’t he heard anything? How could this have happened right in his own home?

John and Patsy looked into each other’s faces, silently sharing a horrible fear. In the middle of the night, someone had entered their home, left a ransom note and taken their daughter. They were too dazed to speak. How was it possible? Wouldn’t they have heard her cry out? Wouldn’t they have heard something? Wouldn’t they?

John quickly rushed through the house, haphazardly checking for anything—something—while Patsy finished placing the 911 call and proceeded to call family and friends to come help them.

One of Patsy’s best friends received a phone call from Patsy, who was screaming into the phone, “Get over here as fast as you can. Something terrible has happened!” (BPD Report #5-402.)1

John’s Journal:

We were out of our minds. I looked under JB’s bed. If I could keep my wits about me I could get her back. She is smart and strong—she knows her Dad will get her back.

A uniformed Boulder police officer arrived in a marked police car within eight minutes of Patsy placing her 911 emergency call. John and Patsy Ramsey had a traditional belief in the police. When you needed help, you called them, and they knew what to do. They were comforted by the officer’s arrival. John showed Officer Rick French the ransom note and tried to explain as clearly as he could what was happening. He told the officer their daughter had been kidnapped. She was only six years old. Officer French listened, took notes and asked John, “Do you think she could have run away?” John said, “No. She’s only six years old. She wouldn’t run away.”

Officer French took a brief look in various areas of the home but reported finding nothing suspicious. Within two minutes, a family friend had arrived, pulling into the alley driveway and then running to the east-side front of the house. Another officer also arrived.

In the moment, the unknown—as cruel as it was—would turn out to be better than the terrible certainty that was coming.

Soon Burke was roused from his bed and dressed so he could be hustled away from the growing turmoil inside his house and go to a friend’s house to play. Both John and Patsy walked with their son down the path in front of their home, accompanied by one of the police officers, to a friend’s waiting car. Bundled in his winter jacket, Burke carried an armful of toys he had received for Christmas just the day before. He was crying. His parents hugged him tightly, trying to convey all the reassurance they could muster.

“JonBenét has been taken but we’re going to get her back,” John told his son. He also told Burke that it would be better if he went to a friend’s home for now, that his mom and dad were there for him and this would all soon be resolved.

After Burke left, the morning wore endlessly on, and Patsy felt her mind slowly closing down. “I was unable to hold onto the fact that my daughter was gone.” All around her, she saw blurred images of kind-faced people, their mouths moving with distant and faint sounds as she sat collapsed on the floor in the Christmas wonderland she had created. The beautiful tree with its shimmering ornaments stood in one corner, yesterday’s symbol of joy not only irrelevant but a brutal reminder of how quickly things had turned. Her agony could not be suppressed.

She vomited into a bowl between her legs.

People continued to arrive. Detectives. Friends. Victim Advocates whom the police had called. Patsy tried to answer everyone’s questions, but to those around her she seemed frozen in slow motion at times and then broke down in out-of-control crying just short moments later. For Patsy, one thought—a stubborn focus—provided a lifeline connection to JonBenét. She felt that as long as she held that thought and let nothing else in, then her daughter was still with her. She had to communicate with JonBenét by concentrating only on her, and she was determined to hold onto that connection. It was a fragile and desperate attempt subject to the sharp realities of the intrusions all around her. Patsy Ramsey was willing her daughter to be there, to hear her. In her anguish, she was trying to hold the world away.

Patsy couldn’t have known this at the time, but in the minds of some of the people moving around her that morning, the roots of suspicion, even of judgment, were already taking hold.

John was in another room. He, too, was

answering questions, trying to offer what help he could. Unlike Patsy, he was allowing his mind to contemplate the terrible realities at hand. John was consumed with thoughts of the kidnappers, of the freezing temperatures and darkness of the night that had just passed, of the fear he had for JonBenét. What was she thinking? Was she crying for her mom and dad?

Were they hurting her?

Was she alive?

He offered the police anything they wanted. What can I do? What do you need? Ask me anything. Anything. Just tell me what you need.

John’s Journal:

We would get JB back & I couldn’t wait to hold her in my arms. The FBI had been called we were told but would take a couple of hours to get here. I wanted to block roads, put police at the airport are we doing enough? We gave the detectives more leads.

We are worried the kidnapper hasn’t called.—Where is the FBI?—We’re told they’re reachable by telephone for advice. I’m thinking who can I call to get all resources on this? I’m getting desperate now.

He tried to focus on the one goal of getting his daughter back. Unspoken, his thoughts tumbled as he wavered between thinking about “when” they’d get JonBenét back versus “if” they’d get her back.

His more optimistic thoughts led to planning how he and Patsy would take JonBenét and Burke away when this was over.

But that was just a wishful daydream that faded as despair seized him. There might not be a happy reunion. There might not be a trip away for JonBenét and Burke to overcome this trauma. Whatever had happened to his daughter, life would never again be “normal.” His thoughts tumbled over themselves all morning.

At one point very early on December 26, there were at least five police officers and two detectives in the Ramsey home. In fact, at varying times throughout the morning, there were a total of eighteen family members, friends and law enforcement personnel on the premises, most freely wandering the home, contaminating the crime scene and whatever evidence might have been there.

John continued his search, which was erratic. He looked in a closet, behind a chair and under a bed, picking up a magazine and even looking in their walk-in refrigerator. In fact, the refrigerator was the first place he looked. And while telling himself to “focus,” he was incapable of an organized and logical search. He was trying to find his daughter, but he didn’t know what else he should be looking for. He was traumatized. By the time John got to the basement, he simply wandered through some rooms, which were messy from the Christmas season preparations, not seeing or knowing what might be out of place until he got to the train room, the room where Burke had set up a model train on a table.

It was there that John Ramsey saw something that terrified him: an open broken window with a suitcase underneath it and a scrape mark on the wall near it.

The suitcase would later be moved from its horizontal position along the wall to a vertical angle, as shown, by a family friend.

That suitcase shouldn’t be there, John thought. The window shouldn’t be open. And what is that scrape on the wall?

He immediately returned upstairs and told an officer what he’d seen. He explained that the window had been broken the summer before, when he’d been locked out of his home. He’d gotten into the house by breaking that window. But the suitcase was normally kept under the basement stairs with the other luggage. And the window shouldn’t have been open. He knew something was very wrong. A Boulder police report added more information: “(sometime before 1000 hours) [10:00 a.m.] John Ramsey went down into the basement to the train room and he found the train room window open so he closed it.” (BPD Report #5-2473.)

Suitcase, which was originally horizontal next to the wall when John said he found it. Courtesy Boulder Police and Boulder County District Attorney.

Detail of possible shoe scrape on wall. Courtesy Boulder Police and Boulder County District Attorney.

The second officer on the scene that morning wrote in his report that he “examined the outside of the residence … initial inspection of the west basement window grate.” (Sergeant Paul Reichenbach—Date of Report 1-26-1996.)

The “west basement window grate” was located above the broken basement window.

The Boulder sergeant also wrote in his report that he “observed actions of occupants of house.”

When the winter sunrise allowed, John grabbed his binoculars and went to one of the highest points in the home on the third floor. He scanned the neighborhood to see if he could spot anything unusual. Perhaps there would be a car, a van, a person, something that struck him as suspicious and might help police.2

He also checked his mail, hoping it might contain a clue. The mail was delivered through a mail slot near the front door that dropped the mail inside the house. Even that well-intended act would be misconstrued, as John Ramsey would later be criticized in a leak to the media for taking time during the crisis to sort through his mail.

At a time when it would seem of critical importance that the family and police should be working in careful concert, the investigation was already teetering on the edge of disaster, like a snow-packed mountain in which unstable particles of snow are shifting beneath the surface, about to cause that first gigantic surface crack, the signal of the beginning of an unimpeded avalanche.

Commander-Sergeant Bob Whitson, the on-call supervisor that morning, didn’t arrive at the Ramsey home until more than three hours after Patsy’s frantic 911 call. Before his arrival, he had gone through a deliberate process of notifying necessary personnel, contacting and setting up a meeting with the FBI, and searching for a recently created kidnapping protocol document that hadn’t yet been distributed to Boulder police officers. Only a few detectives had the document, and they were on vacation over the Christmas holidays.

Even though his arrival was delayed, Whitson knew he needed to observe the scene firsthand and talk with the Ramseys. When he arrived, they were in different rooms of the house.

The sergeant went first to John. To Whitson, John appeared to be a distraught parent who was forcing himself to respond calmly. John was able to answer questions, and Whitson thought he was earnestly trying to contribute.3

JonBenét’s bedroom was the supervisor’s next stop. Whitson walked upstairs to the second floor with the two detectives who’d been on the scene since earlier in the morning. Upon arriving outside the door to JonBenét’s bedroom, Whitson looked in the room for any signs of crime such as blood or broken items, something that wasn’t as it should be. He didn’t find anything. He also had no idea how many people had already traipsed through the little girl’s bedroom. According to his report, he ordered the detectives to block the door with yellow crime scene tape and stressed that no one should go in the room except police. He made a point of telling John that no one but investigators should go into his daughter’s bedroom.

Then, Whitson asked one of the two detectives present, Fred Patterson, to obtain handwriting samples from John and Patsy Ramsey. From a desk located just outside the kitchen in an area near the back staircase, John produced two tablets the family used to write notes to each other. On one tablet that contained samples of John’s own handwriting, John also wrote more at the top for additional comparison. The other tablet contained samples of Patsy’s handwriting.

In his initial police report, Detective Patterson said he “gave the pads to Sgt. Whitson for later comparison with the ransom note. Sgt. Whitson maintained custody of the pads.” Whitson would take them directly to the Boulder Police Department. The ransom note had already been taken to BPD headquarters.

Portion of Commander-Sergeant Whitson’s police report.

Unknown to other on-scene law enforcement personnel, the second of the two detectives, Linda Arndt, kept a sample of John’s handwriting and didn’t submit it to Whitson, who at that point was the custodian for the handwriting collection. This action was contrary to the way a trained investigator or lab processor would collect a significant forensic sample. Accepted forensic protocol dictates the investigator or

processor “selects a team of trained personnel to perform scene processing, collects the evidence at the scene, bags and labels it and then transports it to the lab where scene evidence is being collected.”4 Although there was nothing wrong with someone not specifically designated to collect such evidence doing so at the scene, the manner of the collection was less than scientific and could easily have raised chain-of-custody questions at a later trial, especially when the other officers didn’t know Arndt had kept a sample of John Ramsey’s handwriting.

Sgt. Reichenbach, the second officer on the scene, reported his findings to Whitson. “I was told there was [sic] no signs of forced entry” (Commander-Sergeant Robert Whitson—Date of Report 1-27-1997).

Even though Reichenbach had examined the “west basement window grate,” Whitson did not mention that he had been told this information, or the fact that John Ramsey had reported that he’d found a known broken basement window left open with a suitcase underneath it and a scrape along the wall near it, when he wrote in his report:

Detective Patterson advised me that telephone traps and traces had been placed on the Ramseys’ telephone and a tape recorder was attached in case the suspect called. I was advised that Officer Barry Weiss had already photographed the house and didn’t find any signs of an obvious crime scene where there had been a struggle. (Commander-Sergeant Robert Whitson— Date of Report 1-27-1997.)

We Have Your Daughter

We Have Your Daughter